Dry Flies and Hatches

Camouflage and camouflage breaking are dominant and defining themes among aquatic creatures, at least during the great bulk of their lives--when they are still aquatic. Among aquatic insects whose life cycle includes one or more final instars as flying adults, water column and stream bottom camouflages are no longer much of a factor. Aquatic insects typically live for only a few days once they leave the their watery environment. Evolutionary survival adaptions related to the last stages of the aquatic insect life cycle often include mass synchronized hatching, which helps to insure at least a few adults survive long enough for subsequent mating. Other adaptions exist too, including, at least in some species, hatching at night. But camouflage does not seem to be an important late in life adaption, as it is earlier in their life cycle.

So if camouflage does not play a big role in the dry fly story perhaps accurate, detail-oriented imitation does, at least in the active, ongoing hatch context so many dry fly fishermen seek out and value so greatly.

Snell's Window

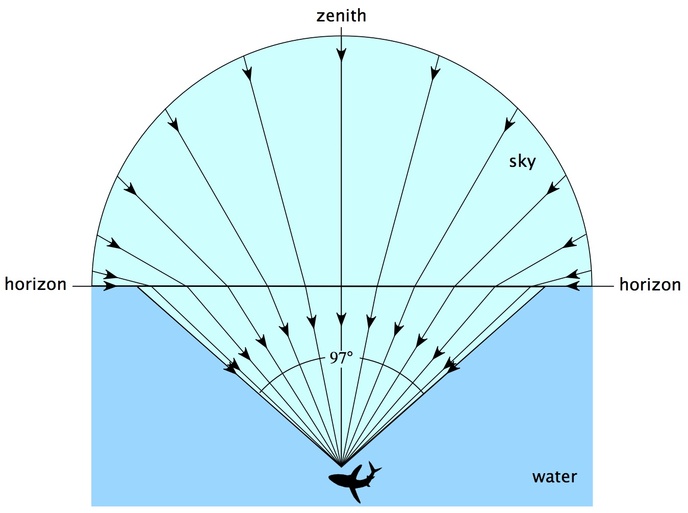

Snell's Window is a good starting point. Because of the way light shining down from above is sharply refracted (bent) by the greater desnsity of water any lens or viewpoint looking up from below, like the eyes of a fish, sees the underside of the surface as a mirror image of what ever is below, all except for a fuzzy-edged circular viewport directly above the fish's eyes. You can think of this viewport as a cone-shaped window starting as a point at the fish's eyes that radiates upward at approximately 97 degrees. If a fish is resting in the water column looking up, everything above looks like a mirror of the bottom below except for a transparent, circular view of all that is above, approximately the same distance wide as the fish's distance down from the surface.

What fish see in the window is everything above from shoreline horizon to shoreline horizon north south east and west, all condensed into a relatively small window. Some online sources (I have not found a written one yet) claim there is a triangular ten to fiteen degree "blind spot" close to the surface that allows predators (fishermen, herons) to crouch down as they approach, without being seen. Perhaps this is nit picking but there technically is no such blind spot.

As the following diagram illustrates, light closest to edges of the window is refracted most. Any images formed close to the edges of the Snell's Window are graphically distorted. Close to the water is not so much a blind spot, it is a maximum distortion area. I think that's an important distinction because, as it turns out, there is a lot more distortion yet to come.

The width of the viewport increases with depth and decreases with proximity to the surface. When fish are only a few inches down from the surface what they can see above is only a few inches wide. When the tip of a fish's mouth is only a half an inch away from a drifting insect, the expected prey is no longer actually visible.

After noticing a characteristic insect-like dimple pattern in the mirror above predatory fish position themselves downstream facing up so the prey approaches automatically, and then they rise vertically upward at just the right speed to intercept the incoming prey, like a little league arm reaching up at just the right time to catch and incoming fly ball.

And Now the Important Part

Ray Bergman speculated the visual appearance of small objects floating on the surface would be backlighted and silhouetted by the brightness of the sky behind.

From the Sunshine and Shadow of Trout by Ray Bergman:

" Under certain circumstances and on clear days trout cannot evaluate either size, color or shape of objects on the surface of the water." And then again one or two sentences later: "Let us hold a a fly directly between the sun and our eye. What happens? Color vanishes, shape is obscured, size becomes an uncertain quantity. "

In addition to back lighted silhouetting additional distorion plays a big role in the dry fly story too. Toward the center of the window images do appear less distorted than at the edges, if and only if the surface is perfectly calm clear and flat. Currents, ripples, waves and drifting vegetable matter all refract light in different directions. Fish see well enough to tentatively recognize interesting incoming prey images but there is no sharply-focused, fine-grained view of anything.

Spring creeks and shallow slicks at the edges of our bigger tail water rivers provide the sharpest view of the world above but even there what fish actually see are fuzzy-edged silhouettes with possibly familiar outlines. In fast water riffles a fuzzball shadow is as good as it gets. Fish do get suspicious, spooky and hard to catch. About that there is no question at all. But what ever it is that sets them off is not sharply-focused fine-grained detail. Fish can sometimes see sharp detail below the surface. But not so above.

In a peer reviewed paper first published in January 2023, in the highly-regarded Linnaen Society, T.E. Reimchen describes a series of submerged camera experiments quantifiying visual distortion caused by both currents and waves. In rapid current riffles forget it. A fuzzy outline is all a fish can see, no matter what. In calmer, slicker waters, as is so often the case in gin clear pring creek or tail water aquatic insect hatches, fish see all that is above but not as sharply as they see objects below the surface.

The status quo for visual distortion through what Reimchen refers to as the "air water interface" so often includes wavy, light/dark obfuscating ripple patterns, Reimchen suggests prey bird species like Plovers and Killdeer may have evolved their characteristic wavy striped chest coloring patterns, in order to help them blend into obscurity above, as they staik small fish below. The view through the air water interface involves visual distortion in both directions, effecting what bird predators see as they look down, and what insectivorous predators see as they look up. What they do actually see is enough to survive on. But not as function of fine-grained visual certaintly. The air/water interface inevitably leads to what amounts to guessing and intuition in most cases.

Who Refuses What and Why

In A Modern Dry Fly Code Vincent Marinaro describes trout repeatedly refusing one of his artificial imitations. A fish might swim up to close to a fly, change its mind and turn away, change its mind and turn back to the surface again several times in a row. The last iteration of a compound refusal ends either with a take or a final a rejection. That's temptation, confusion and indecision at work, all at the same time. We've all seen that happen with dry flies.

Every spring creek guide I know has seen compound refusal at work for real mayflies too. This is not an isolated incident only a few of us have noticed. Every spring creek guide I've ever talked to has seen it at least a few times. My good buddy Chuck Tusschmidt has even seen it at work on his favorite central Montana tall water fishery. The venerable George Kelly--currently the Dean of all Montana fishing guides--has seen real mayfly refusal at work on his favorite Eastern Montana tail water river.

Conclusions implied by compound refusal of floating, real aquatic insects are complex and not at all obvious. When I first saw it I immediately assumed real trout refusing real mayflies was not a natural phenomenon--that this was entirely a function of over-fishing. George Kelly, my most experienced, most respected and most trusted of all sources told me he too assumes real insect refusal is associated with fishing pressure, for the most part. But George also told me to be careful about my conclusions because he has seen real trout rise up and ultimately refuse real midges in wild high altitude lakes, where fishing pressure is not in any way a factor. When George first told me that it hit me like a bowling ball shot from a canon. What is going on here?

What Do We Know?

In clear water fish see better below the surface than above. What fish see above the surface appears in an ever expnding and shrinking Snell's Window. The closer fish are to the surface the smaller that window is. Moments before they inhale the window is so small they see virtually nothing at all. Snell's Window is always fuzzy and distorted at the edges. Closer to the center of the window images are represented more clearly, if and only if the surface is dead calm and flat, which it rarely is. Visual distortion is at its greatest in fast, broken mid-river riffles or on windy, choppy days. Above the surface vision is at its best in smooth flat water spring creek or tail water slicks. But even there what fish see is not as clear as below and likely back lighted into a sihouette too boot.

When i look at an an artificial fly I know instantly and with abosolute confidence it is not real. For floating insects the same conclusion is not so certain for real fish. Fish often, at the last moment, refuse artificial imitations. But they sometimes refuse real ones too. Spooky fish are easiest to catch in broken waters and hardest to catch in smooth. But even there they sometimes fefuse real insects as well as fake ones. Fish have strong instinctual urges to feed and to prosper, but also to fear and to survive.

The secret to catching more fish with dry flies, if there is one, cannot more accurate, more fine-grained, more precise detail when wary fish are all too often confused and uncertain about the real thing. If there is any secret at all it has more to do with carefully, gently presented and sparsely tied imiations of vaguely the right size and color. And not anything at all to do with precise detail and imitation.

Size and Color

So if precise profile and detail are not a factor what about color and size? Size does clearly matter, at least in the case of a thick, ongoing mayfly hatch. That was my experience as a fisherman and as a guide, and almost everybody else's too. Has anyone ever argued fly size was not important? Color at this point in the discussion might matter too. It might, but if so not as much as size.

How important is color? I'm not really sure. When ever a customer ran out of Pale Morning Dun patterns, on the spring creeks, I put on a Blue Winged Olive and he or she never missed a beat. A March Brown might not be a good Pale Morning Dun substitute but a March Brown is a substantially bigger Mayfly. Too big matters a lot more than too small. When frequent refusals do happen it's clear something seemed wrong to the suspicious fish, but it isn't entirely clear exactly what it is that puts them off.

The Pale Morning Dun Story

Another argument against color as a critically important factor includes the Rocky Mountain States Pale Morning Dun story. If color really mattered the Pale Morning Dun story would need some serious editing. I tell my version of the Pale Morning Dun story in the Spring Creek Flies chapter.

Most PMD fishermen use small yellow dry flies or emergers. Yellow is interesting because only the male PMDs are yellow and they do leave the habitat almost the instant they hit the surface. I Male PMDs wiggle furiously and spin left and right as they drift, but seldom float for more than 12 to 24" inches on the surface before they fly off. After that they're away from the water for the rest of the day. Male PMDs are highly active and they do fly over the water all day long so they're the ones you see. But once airborne they are never in contact with the water again. Not until after mating time anyway. The slightly larger and substantially more lethargic olive colored females are the ones that ride the surface for 20' feet or more. You never see the females after they fly. They go straight to the willow bushes and perch there motionlessly until mating time arrives. Nobody fishes olive PMDs and yet they're the ones the fish are gobbling off the surface. Yes males get eaten too but far fewer because they fly off so quickly. Upright adult males are not there on the surface long enough to get eaten as frequently as the slower moving females.

The Big Picture

As mentioned earlier, if you run out of PMD patterns in the middle of a hatch you can switch to smaller grayer Blue Winged Olive imitations and never miss a beat. Mimicking dry fly color does not hurt your chances, but it is not at all clear how much it helps. Matching the Hatch is important to some degree. But only during a hatch and too big seems to matter a lot more than too small. Royal Wulffs do not work well at all. That is true. But a large variety of shapes colorings and sizes ranging from a bit too big to a bit too small do work. They work well too. It's also worth pointing out small not-weighted soft hackle wet flies can be absolutely deadly during a PMD hatch. As a guide I can't remember a single customer who came wanting or expecting to fish with soft hackle wet flies during a PMD hatch. But I often put them on when it seemed time to change flies. Soft hackle wet flies are a goto fly for me during a hatch, especially so during Fall Baetis.

Fly size and vaguely the right color is easy to get right for any given hatch situation. But real hatches are relatively rare. Most of the time we fishermen have to deal with coaxing reluctant fish fish rather than eager ones. When there is a hatch, and when the fish dimpling all around us are still hard to catch, what is really going on? In the Western USA States there has been a gradual fly design evolution toward mayfly and caddis dry flies that perch closer and more parallel to the water's surface. Rene Harrop no hackle duns, parachute patterns and Sparkle Duns now sell better than traditional high-riding Catskill dressings. The differences are real I think, but small.

Fishermen tend to focus with laser intensity on their drifting flies. Fishing makes it hard to soak in the bigger picture. A spring creek guide has a bit more time on his hands than his clients. In between netting fish and changing flies I couldn't help notice real flies seldom get refused. Real flies do occasionally get refused, but rarely and only on the most heavily and intensely fished waters. I have seen a fish "compound refuse" a real mayfly once or twice, on Nelson's Spring Creek and at Depuy Spring Creek in the Yellowstone River Valley for instance I . But for the most part real mayflies get eaten, almost every time. Perhaps the answer is there right in front of us--like the Emperor's new clothes. Real mayflies look a lot like mayflies while our feathery hooks do not. It doesn't take me long to know whether I'm looking at a real mayfly or a hand-tied artificial. Maybe the fish can too, especially so after they've been caught a few times. Perhaps it's it's a minor miracle we ever catch fish at all. Perhaps severe backlighting in the Snell's Window is the only thing keeping us in the dry fly game.

What Matters Most?

So far I've proposed dry fly size is important, during an active hatch, while the roles of color and silhouette might matter too but if so less less so. What matters most of all is the fishermen. Call it Chi, Moxey or Aura, what ever it is some fishermen have it in spades and others do not. My lifelong fishing buddy Patrick Jobes has consistently out-fished me for the past 40 years while using some of the fuzziest, ugliest flies known to Western Civilization. It's worth mentioning too that Moxey is not the same as presentation. Casting skills can be learned and refined. The predatory eyes ears instincts and reflexes of the hunter are bequeathed at birth. We have to live with who we are and to make the best of it. You could fish for a hundred years and never catch up to George Anderson. The Universe does have certain fundamental rules that cannot be altered or changed. Moxey is one of them.

None of that discounts the obvious importance of what so many writers refer to as 'presentation.' Practice and skills matter almost as much as Moxey. Years of coaching, long hours of film sessions and on-court experience gradually and inevitably improves basketball players like Jamal Mashburn or Ben Simmons. But it never turns them into Michael Jordon. At playoff time Michael, Magic, Koby, Larry and Akeem matter most of all.

Elaborate, sometimes complex fly tying is fun. Fly tying has been and continues to be a lifelong hobby for me. But I know with great certainty my old friend Patrick will out-fish me the next time we meet on a stream. And Patrick never has much more than a few old time standards in his box, like Gray Hackle Yellow, Parachute Adams, George's Brown Stone, bead head Zug Bug, Latex Caddis and maybe a Yellow Sally or two. And none of them well tied.

With almost equal certainty I feel confident my creative fly collection helps me to keep that disparity in check. If Patrick had access to my fly boxes I would be left even further behind. Cool flies help. A little anyway. The fisherman makes the biggest difference of all.

Notes:

I Lewis and Clark on the Jeff...they found trout but could not catch